Amy Sherald on Her "Gentle Presentation of Black Identity" and More

Sherald, who has a solo show at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, shares her reasons for painting and what's next for her career.

ST. LOUIS — On the opening night of her exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Amy Sherald is jubilant, albeit being pulled back and forth by museum staff and obliging cordially as person after person requests a photo or a conversation. It is Sherald’s first major solo exhibition since the unveiling of her portrait of Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery in February.

As she prepares to leave for dinner, a man asks if he can take a picture of her with his daughter. While awaiting the man and his daughter, she and I discuss St. Louis, the similarities between here and Baltimore, where she lives — how both cities are still attempting to overcome issues such as segregation and discriminatory housing practices. As the conversation becomes more impassioned with our critiques of each respective city, I see the father return holding his daughter’s hand and I motion to Sherald that she is now ready. As the father steadies his cell phone to take the photograph, Sherald gently places her hand on the little girl’s shoulder, who grins wildly. I also smile, realizing that while her innocence and juvenility might obscure her understanding of this moment, the girl will always have this image that symbolizes so much more. She is standing next to someone who looks like her and who represents the possibility of what she could one day become. She is standing next to the artist of 2018, who perhaps will become one of the most memorable of the past decade. The woman who in February unveiled a portrait of the first Black First Lady of the United States — who herself was and continues to be an emblem of possibility and a new ideal — and now has new gallery representation, an increased demand for her works, and has been thrust into the spotlight after being relatively under the radar.

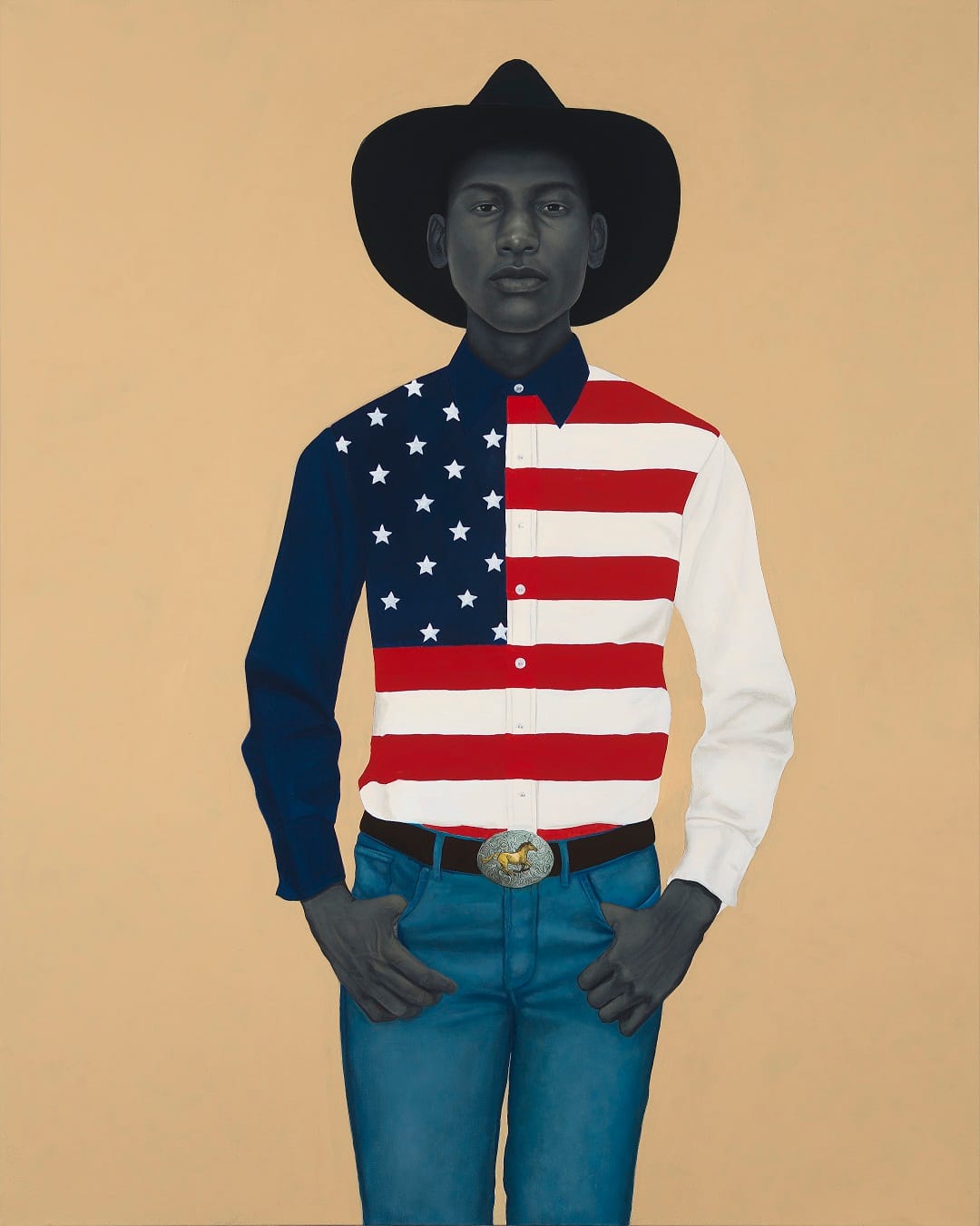

Sherald’s work is concerned with how Black people show up in the world everyday. For this show, which features seven paintings in total, she has created two new works. One, titled “Planes, rockets, and the space in between” (2018), is a departure from the other portraits on display, which feature her subjects painted against a solid-colored backdrop. In “Planes,” however, Sherald has painted two girls who stand barefoot in a field holding hands. One girl wears a multi-colored dress, her hair styled into a bun atop her head complemented by a white hair tie fashioned into a bow. She looks back at the viewer, as if she hears them approaching. The other girl stands uninterrupted in a white T-shirt and mini denim skirt. Her gaze stays fixated on what’s in front her — in the distance, a rocket has just launched leaving a cloud of smoke in its tracks. In Sherald’s second new painting, “Untitled” (2018), she has painted a stylish, full-bodied woman with an abundance of curls in a navy-blue dress designed with a print of lemons, and I am immediately reminded of Beyonce Knowles’s 2016 album Lemonade. I look at the work for quite some time and consider the power and impact of Black women creating art of the times that reflects not just pain and struggle, but also overcoming and victory. Lemonade provided Black women with anthems for reclaiming their narrative, taking up space and encouragement to self-author a history often keen on ensuring their absence. In Sherald’s portrait I come to recognize the sanctity of Black womanhood and the necessity for care that the artist brings to her portraits.

As Sherald and I sit down for an interview after the press preview, we discuss her impact, the significance of Black cultural production, the importance of communion and fellowship among Black people, and what’s next for her career after her work has become such a defining moment in history.

* * *

Rikki Byrd: This is your first exhibition since the unveiling of your Michelle Obama portrait. It’s also being noted as your first major solo exhibition outside of your show in 2016 at the Monique Meloche gallery in Chicago. How is this show different than the one in 2016?

Amy Sherald: What’s different is that I have a painting in there that’s kind of a transitional painting. Other than that it’s not really that much different. It’s just that it’s in a museum.

RB: Do you have any expectations for this show or any expectations you’ve set for yourself?

AS: I mean, I did the work, and it’s here now and I emotionally let go. For me, right now, it’s just important to take a breather. Because when you’re painting, you’re really insular and I just want to be out and be in the world and be a civilian for a little bit before I go back into my Batwoman cave.

RB: During the unveiling of your portrait of Mrs. Obama, she said that you were well on your way to becoming the artist of your generation, and it seems like you already are. Your work has been referenced on social media timelines far and wide — a little girl who’s two years old looked up at your painting of Michelle Obama and called her a queen; the series finale of Scandal referenced the impact and velocity of your work. What has it been like to navigate that spotlight and carry the weight of this legacy that you’ve now left?

AS: People say that. It’s hard to feel it in the moment. It was a historical moment, but it doesn’t feel that way yet. I feel like I need 10 years to look back. I always joke around and say when I’m 70 years old and when I’m getting my NAACP image award, then I’ll look back and be like “I did that.” But for me, [I’m] getting used to notoriety because along with that come people who think that they can talk to you however they want to talk to you and that they deserve to have access to you all of a sudden. So, that’s been an interesting part of it. I do appreciate the young fans that I have now because that’s really special. Like visiting classrooms and they’re super geeked that you’re there. They can’t keep still. I shared a video on my Instagram of that and I put hashtag “I’m not a basketball player,” hashtag “I’m not a rapper” because to me that’s a special moment because their minds are opening up to seeing that they can do things. So, just having the power to expand the minds of our youth is really the best part about all of this.

RB: Prior to being selected as the artist to paint Mrs. Obama, in 2016 you won the Outwin Boochever prize and you were the first woman to win that prize. I also want to add you’re a Black woman receiving these accolades. I want to talk a little bit about the experiences of being, at times, the only Black person in these predominantly white spaces and also about Black womanhood. How do you navigate your identity alongside your work?

AS: I just go into these spaces as myself. The work goes in as a representation of who I am. I think the work sits in the world in the same way that I do where it’s not in your face, but there’s a lot of subversive messages happening, and they are diplomatically presenting a corrective narrative. I guess in that moment of winning the prize, I don’t know. That’s a hard question to answer because I live my life as an artist first. I feel like, for me, I have such a community of Black artists around me — access to them — that I don’t feel like the only Black person in the room. And my micronarrative — if I look at the art world in general — I know where I belong, so you know that there are certain galleries that represent the top Black artists. Those are the ones you’re going to shoot for. But there’s also the galleries that don’t really represent a lot of Black artists, so it’s kind of easy to know where you’re going to fit in. It’s going to be Jack Shainman. It’s going to be Tilton. It’s going to be Roberts. It’s going to be Galerie Lelong. So you kind of know that you need to be in touch with people like Thelma Golden because the world is a lot smaller for us, which in some ways might make it easier. Because when I look at my career, and I look at Black women who are figurative painters, I can probably count less than 10 in the whole world, which is kind of insane. We’re not growing up in West Baltimore saying “I want to be an artist,” and if they are, it’s squashed by the time they’re in the 11th grade. It’s not a reality. I’m hoping that with my presence as a Black woman in the art world that those kinds of things can change, too.

RB: To add to your point about community and fellowship, the unveiling of your portrait alongside Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama came at a very special and particular moment: Black History Month. At the the top of the week your portraits were unveiled and by the end of the week, we had Black Panther. It was really one of the best Black History Month’s I know I’ve had.

AS: I know. I felt that, too. I really wanted to say, when I gave my talk [during the unveiling at the National Portrait Gallery], “This is the blackest day ever.”

RB: It was! And on Twitter, we were uniting under the hashtag — this kind of digital community — #BlackHistoryMonthSoLit, #BlackPantherSoLit.

AS: It was definitely a moment of fellowship.

RB: Absolutely. In the midst of this era of Black Lives Matter, black pain, and black trauma that Black people are constantly waging against, it was a moment to exhale. Your depiction of Michelle Obama. Kehinde Wiley’s depiction of Barack Obama, and then Black Panther ushering us into this imaginative African nation, [there was] this fantasy being created that we could kind of live in for a moment. In this era of Black Lives Matter, Me Too, Times Up, what does it mean to you to be a Black artist creating art of the times and to be depicting Black people specifically?

AS: Well, for me what’s important about the work is that it is a place where we can exhale. I think that’s really important that all images that we see of each other — because we see so many different things in the media — that it’s nice to come into a space and see yourself expressed gently and just being able to sit with that. I think a lot of things that we consider fantasy are really what the Black interior space is like, how we live inside of ourselves. I think that movie [Black Panther] is an expression of that. It’s difficult to expand our notion of identity when it’s constantly in a reactionary space because of things that are happening, because of Black Lives Matter, because of Me Too, because of all those things. It feels very complicated to want to explore yourself and your identity outside of that because we’re not free if everybody’s not free, right? There’s a sense of being connected in that way because of that. I think that’s a struggle of mine of wanting to release and get to know Amy outside of all the codifications. I grew up and my mom told me you’re going to be a Christian, you’re going to worship Jesus, you’re a woman. She didn’t express my limitations, but the world kind of told me what my limitations were: “You’re black. These are your limitations.” I began to push back in my 30s, deconstructing religion, like, “This doesn’t make sense.” So let’s think about race. It’s a construction. What intersections do I want to live inside of that and what do I need to let go. Because what parts of those are just colonizing my mind? And how can I stay connected to the movement and be colonized at the same time?

RB: I read that you were inspired by W.E.B. Du Bois and his compilation of images of Black people after the Civil War. He created these albums for the Paris Exposition in 1900 to combat these stereotypes and derogatory images [of Black people]. Do you think that those intentions are present in your work?

AS: Oh, for sure. It was a huge affirmation to see his work. Even then, when you think about respectability politics and when I consider performance and identity, it’s still a performance for the gaze. It was a performance to prove our own self-worth. I really considered that in the portraits because I don’t want them to have to compromise. They’re not compromised in any way. They’re not concerned with performing.

RB: There’s a care that’s there when I view your portraits online and I was emotional viewing them today. I know that care taking is a part of your story. You’ve spoken on end about leaving Baltimore to return to Georgia to take care of your family. Can you talk a little bit about how care taking shows up in your work?

AS: In a sense I try to take care of the viewer, to see a self reflected back. That’s a loving self, a gentle presentation of Black identity. So I guess it would crossover to the work in that way. But care taking is something that satiates something inside of me. I didn’t miss painting when I was doing that [taking care of my family] because it comes from the same place.

RB: What about self-care? I know you’ve spoken about your health issues, but also you’re grappling with this maximized interest in you and your work. As Black folks and Black women are left out of conversations about self-care often, how are you returning to yourself? How are you sustaining and maintaining and showing up for yourself?

AS: It’s hard to do and I didn’t do it. You have intentions to do it. Everybody’s talking about self-care, but you wake up and you skip the gym to get to the studio early. I got sick as soon as Michelle [Obama] left the studio. The next day it’s like the adrenaline left my body and I was in the hospital for three days. That was my lesson. I had been working, working, working, and it’s almost impossible to even enjoy what’s happening because you’re pushed to meet the demands of the market. Everything becomes rushed. Each day becomes rushed to the point where you’re not giving yourself an hour. Like, I can give myself an hour to go to the gym. So these past years, everything has started to deteriorate and I think I just reached my breaking point with the completion of this exhibition where I’m like, I have to stop. No more seven days a week. No more 14 hours days. I have to pace this out and find my equilibrium and figure out how to not die in the process. Your priorities change. I’m in the process of making sure that that is something that is maintained and that’s a part of practice and a part of my lifestyle.

RB: After creating something of this scale and this impact, one of the underscoring questions is always, what’s next?

AS: I have my first solo show with Hauser & Wirth in September [2019] and I’m waiting to hear back on another commission, but I can’t say who it is. For me it’s about enjoying my summer. I’m not even thinking about work right now. And then slowly putting together the ideas that I have for the Hauser show because they’re going to be really big paintings and making sure that I am leaving enough time to find those models and getting all of that together. So those are the things that are percolating now. And that’s my first New York show, so it’s another seminal moment in my career. Who knows? I just take it one day at a time.

Amy Sherald continues at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (3750 Washington Blvd, St. Louis, Mo.) through August 19.